![]()

I almost missed it. After exploring Whitby Abbey and the fascinating St. Mary’s Church, I descended the famous 199 steps to roam among the shops of the old town. By pure chance, instead of heading to the multiple displays of jet and seaside tourist trinkets, I decided to take a right turn, keen to view the cottages that lined a tiny street. And there it was. You notice the smell first. And then a sign on the wall: Fortune’s Whitby Cured Kippers. Next to the tiny storefront, doors open to reveal row upon row of herrings, carefully curing until they have become the perfect kipper.

As with so many fishy foods, the kipper seems to inspire a love-it-or-hate-it relationship. Its intense aroma and strong flavour, which tends to repeat throughout the day, can be too much for some. But for others, that smell and taste are just what makes the kipper such a perfect breakfast.

Since 1872, the descendants of William Fortune have been smoking herring in Whitby. Still in the original building on Henrietta Street, it remains the North Yorkshire town’s only traditional smokehouse. You will find its kippers on the menu of most local hotels and guesthouses.

No one knows the true origins of the kipper – where or how the process of smoking fish began. Typical stories are of someone leaving their fish too close to the embers of the fire and then realising how delicious it was. One 16th century story tells just this tale of a man in Great Yarmouth, while some smokehouses have their own origin stories, claiming accidental discovery in the 19th century. In truth, the practice of smoking fish certainly began before the 1800s, probably many centuries earlier, when salting and smoking became common ways of storing fresh foods.

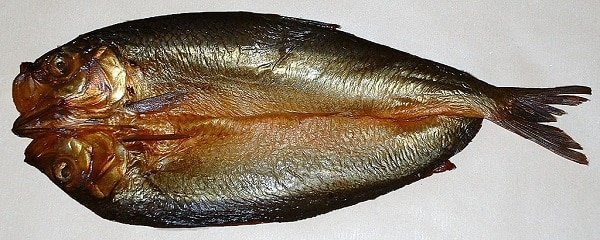

But how are kippers prepared? The herring are butterflied or split lengthwise and gutted by hand, before being soaked in brine. This soaking helps to enhance the flavour. During the First World War, some smokers added dye to their fish, giving the deep colour of a smoked fish but without the lengthy processing time. Some commercial producers still use a dye, although many do not, preferring the golden brown that develops naturally during curing. After soaking, the fish are hung on rods and smoked for about 18 hours.

Kippers used to be enjoyed for tea, but are now found most often on the breakfast plate. Grill or poach them and enjoy on buttered toast with an egg. They also add a wonderfully rich taste to kedgeree or risotto. In the 1970s, the kipper developed a bit of a reputation as old-fashioned and fell out of favour. However, in the past decade or so, they have seen a resurgence in popularity, particularly since they are both sustainable and rich in those all-important Omega-3 fatty acids. They also tend to be much more affordable than some forms of smoked fish.

Where to buy:

You can find kippers fairly easily in your local supermarket. Alternatively, if you want to enjoy some of the finest smoked fish, you can order from a number of smokehouses around the British Isles. These include:

L. Robson & Sons, home of the Craster kipper. The Craster smokehouse was built in 1856 in the Northumberland fishing village of the same name. in 1890, the Robson family bought it, and they opened their doors in 1906. This fourth-generation family business sells both kippers and salmon smoked over oak. Delivery is free to the mainland UK.

J. Lawrie & Sons of Mallaig. Mallaig in the Scottish Highlands was once a bustling fishing town and the busiest herring port in Europe. Today only one traditional smokehouse is still in business. J. Lawrie, or Jaffy’s, produces award-winning kippers, cured over old whisky barrels in a wind-powered brick kiln.

Swallow Fish. Located in Seahouses, Northumberland, the Swallow Fish smokehouses have been in operation since 1843. The owners still use traditional methods to produce a variety of smoked fish and seafood.

Food of the gods! I first tried one when I was about ten – and, 47 years on, I still love ’em.